Work in the vineyards in winter

During winter, the vines enter a dormant state. This is when the essential operation of pruning takes place. The skill of this art requires dexterity and experience and it cannot be rushed.

Read more Close

Read more Close

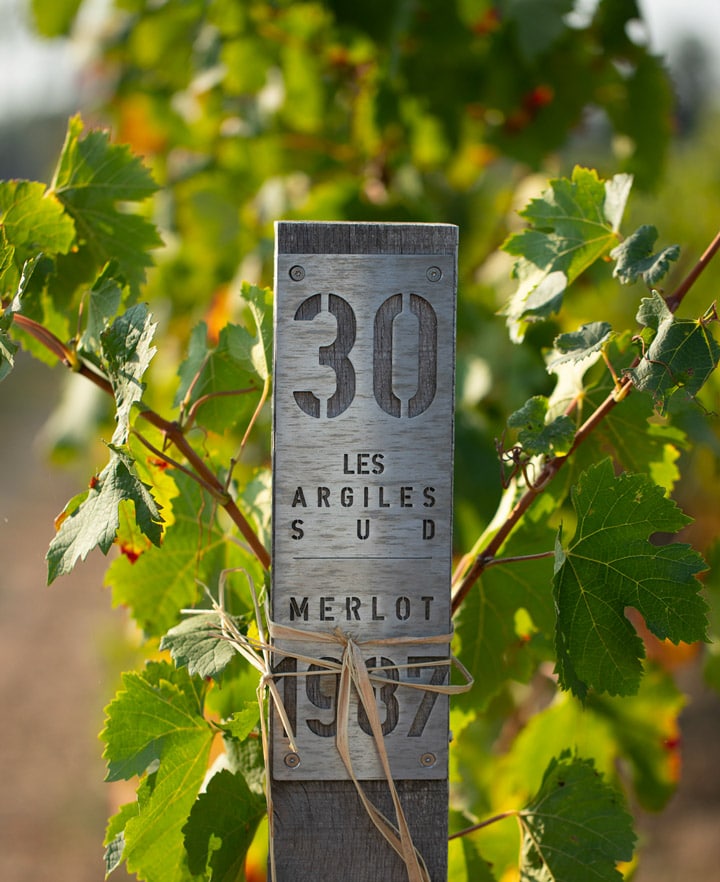

At Cheval Blanc, each plot has its own dedicated pruner. The wine grower examines each plant before sculpting it, respecting its balance and the flow of its sap. Depending upon what he sees, he selects one of the year’s bud-carrying shoots and cuts off the other branches. Depending upon the potential of each vine, the pruner decides on the number of buds to leave on the plant. This ‘disbudding’ will even out the harvest, bearing in mind that each bud will produce two bunches of grapes on average.

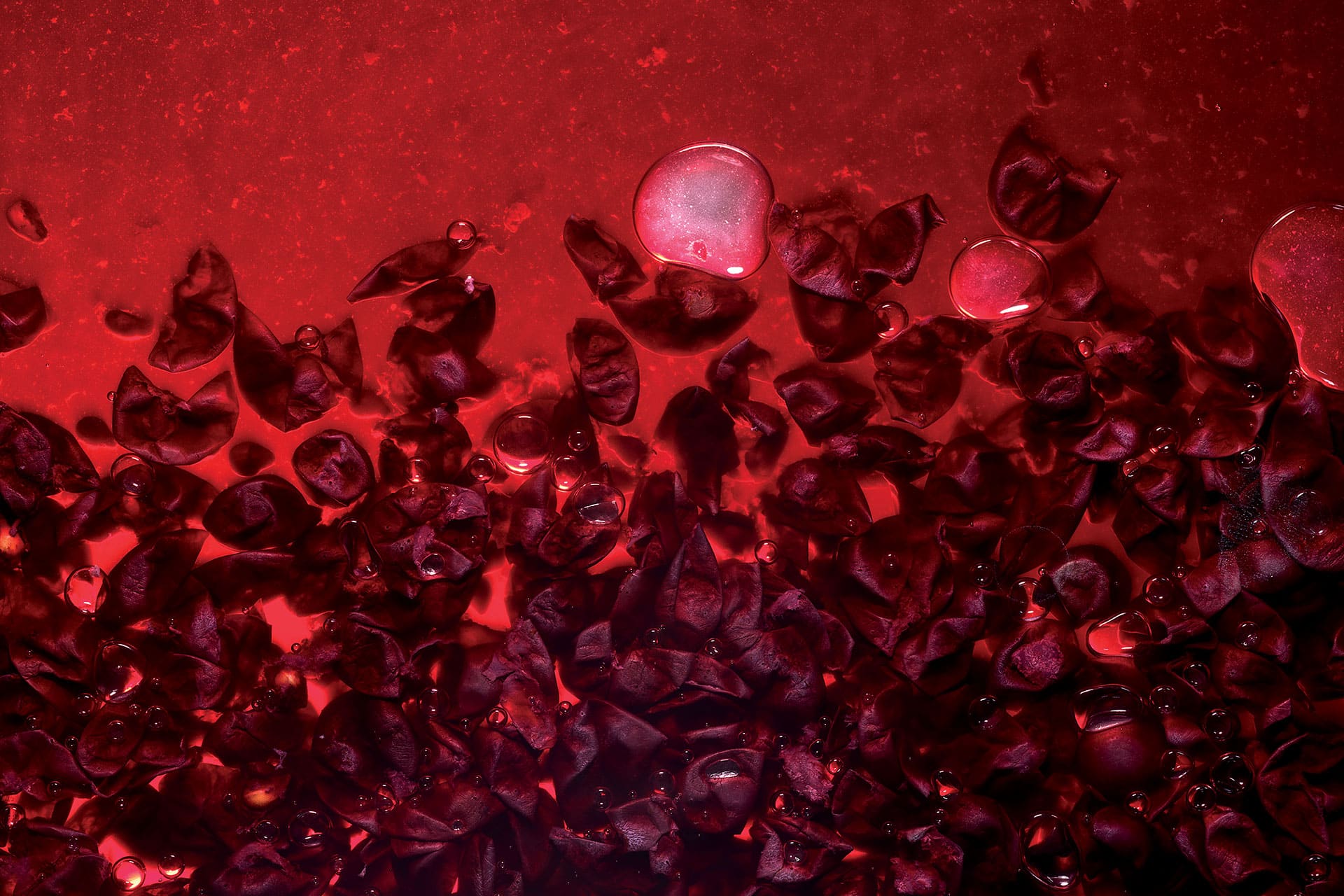

After the harvest, a mix of grass and legume seeds are sewn in between the rows and begin to grow. During winter, these inter-row crops are ‘flattened and rolled’. Withered flowers, leaves and stems will produce green fertilizer to nourish and maintain the life of the soil.

Although we no longer plough our soils thanks to the vegetal cover, we do practice light earthing and unearthing of a strip of soil of 30 cm below each vine. This gentle practice maintains a microclimate which promotes the health of the vine as well as the ripening of the grapes.

Close